"The Dividual" by Mina Ikemoto Ghosh

If you could "cut away" undesirable aspects of your personality, would you do it?

AWARDS:

Rated "Most Popular Fiction Magazine 2024" by Chill Subs

Rated "Top 10 LitMag of 2023, 2024" by Chill Subs

Rated #1 "The Very Best Literary Magazine" by Ranker

Rated “Top 50 Fiction" on Substack

NEWS:

After Dinner Conversation is now offering advertising opportunities right here on Substack, as well as in the magazine and on our social media platforms. Here are the details.

Volunteer as an acquisition reader and help us decide which story submissions get published. No experience required, just a keen eye for stories that make you think. If you’re interested, just shoot Kolby an email and he’ll get you set up.

Educators, find out how to get a free copy of a themed edition.

If you enjoy these stories and want to support writers and what we do, you can always subscribe to our monthly magazine via our website (digital or print), or via substack.

Also check out our free partner ebook downloads.

Thanks for reading, sharing, and re-stacking this post!

Tina

Take the poll for this week’s story, “The Dividual“:

(It’s completely anonymous…and fun!)

Last week’s poll results:

The Dividual by Mina Ikemoto Ghosh

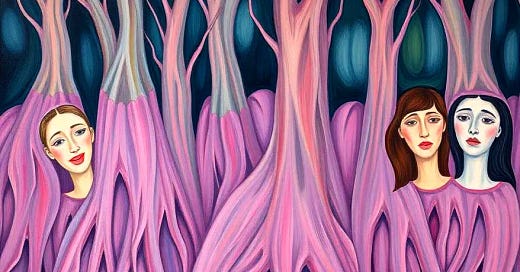

The first dividual I saw I was six, holding my uncle’s hand in immigrations. Ahead of us was a group of seven men and women, blue masks covering their heads and shoulders. They carried between them a pale violet tree trunk, its roots bundled in a burlap sack. I’d never seen a dividual’s heart pillar before.

Each person in that group had had a cord, violet and fleshy, connecting them to their tree. Sprouting from the smalls of their backs, they’d rippled like so many kite strings, and that should have been my clue that these ‘people’ weren’t ‘people’ at all, but ‘personas’—the personas of a dividual human.

Homo dividensis, the species of human with a different face for every facet of their existence.

My uncle had caught me staring.

They’re not like us, he had said.

It had been so easy to believe him then.

In my final year as a medical student, I secured an elective placement in Splint, the dividual city. I was to stay for that period with a dividual junior doctor.

Osqaris Saille’s house had a pebbled front. Glass beads, fossils and shells had been arranged in a swirling pattern, so that the house could be identified at the touch of a dividual tendril.

“Seizo Hanaoka?” said the persona who opened the door.

“Yes, that’s me.” I bowed my head. “Pleased to meet you, Doctor Saille. Thank you for arranging this opportunity for me.”

“It’s an opportunity for myself as much as for you.” They broke into a smile that showed teeth and gums the same pale violet as their skin, lips, hair and the houses of Splint. “Osqaris will do.”

The persona Osqaris Saille had presented to me was welcoming and interested, designed to make a good first impression of professional competence as well as friendliness.

I stared. I couldn’t help it. Osqaris’ features shifted like the satellite footage of Mars’ dunes. Their nose, cheekbones, profile rippled with the flux of ichor beneath their skin.

My own face should have been still, but it didn’t feel that way. The longer I stood on Osqaris’ doorstep, the more conscious I became of the crowd I was behind my eyes. Parts of me squirmed to hide from Osqaris’ studying gaze. Other parts urged me to give in to curiosity and step closer: Study back, like I’d come for.

They’re not like us.

Osqaris laughed.

“It’s not the done thing in Splint to show all of our selves on meeting, either.”

“Oh. Right.”

They winked. My cheeks warmed. “Call it a cultural taboo. I wouldn’t expect it of one of our own, so I wouldn’t expect it of an undivided. Even if you can’t help but carry all your personas with you at once.”

“That’s generous of you.”

“It must be so difficult keeping them all separate. I should think I’d muddle them very quickly if I were an undivided.” They held out their hand. “I’ll look forward to observing you, Seizo.”

“Likewise.”

The price of my placement in Splint was the agreement to be watched and studied.

I took Osqaris’ hand, and paused. The average dividual was six degrees cooler than the undivided human.

Osqaris’ hand didn’t strike me as notably cooler than my own. My body temperature sat squarely in the middle, three degrees above a dividual’s, three below an undivided.

I let go quickly, not because Osqaris’ hand had the tenuous elasticity of a water balloon, but because they too paused, glancing down at our hands.

In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin dedicated a whole chapter to the dividual human. He wrote them to be a kind of land-dwelling octopus, pointing out, as evidence, the octopus-body-like shape of the dividual heart pillar and the tentacular nature of the tendrils, at the ends of the first edition’s illustrations, he had drawn doll-like miniature humans to represent their personas.

Darwin had written that dividuals had evolved ‘humanoid’ features in parallel with undivided humans. The thought at the time had been that dividuals were man-eaters, so the co-evolution had come about to lure unwary ‘true’ humans into their lairs.

It wasn’t difficult to see why Darwin thought the dividuals were sea creatures. Their blood salinity level was closer to seawater than undivided human plasma. They had neural tissue at the end of every tendril for storing personality quirks for individual personas. Their heart pillars were rooted in wells of saltwater, as it was the saltwater pumped around the tendrils that let them inflate and deflate their personas as needed.

I thought Osqaris might test me on our physiological differences in my first morning, studying how I might react when our differences were thrown into my face.

Here are our differences, undivided student medic. Let me hear you preach that common humanity.

But instead, Osqaris simply poured tea for us both, explained my role and responsibilities on my placement, then with a soft smile began asking me about undivided society.

They were curious about persona maintenance when individuals were at work. What happened, they asked, when a professional persona became muddled with a personal one? And how did society manage all the risks that entailed (I told him that society simply didn’t)? They wanted to know about undivided genders. What effect did the insistence that a person must state whether their personas were majority masculine or feminine in their codes of conduct have upon the community? Dividuals were more often blended multitudes of, what to undivided eyes, would be masculine and feminine personas. They categorized themselves only in ‘reproductive relationships’ either as ‘microgametic’ or ‘macrogametic’. I, myself, had ticked a box at immigrations to indicate I was a ‘microgametic persona majority male’ with, admittedly, somewhat mixed feelings.

I contributed what I could. I didn’t think Osqaris was entirely convinced by my answers.

At length I asked, “Osqaris, can a persona be cut away?”

Osqaris paused. “Do you mean amputated deliberately?”

“Yes.”

“It was a regular process here up until the nineteenth century. It was seen as something of a community duty to sacrifice a persona to serving it. We used to use them as messengers between houses and run errands. We didn’t always have a ready supply of undivideds coming to Splint for work, you know. Especially when you all thought we’d drag you into our heart pillar wells to eat you alive.”

“But how did it affect them?”

“The unwanted persona?”

“You, as a whole person. Wouldn’t it be like cutting away a piece of your mind?”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to After Dinner Conversation - Philosophy | Ethics Short Story to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.