Q&A with philosophical fiction author, Edward Hamlin

A bite-sized interview for your Sunday morning.

If you would like to be profiled in this newsletter, here’s how.

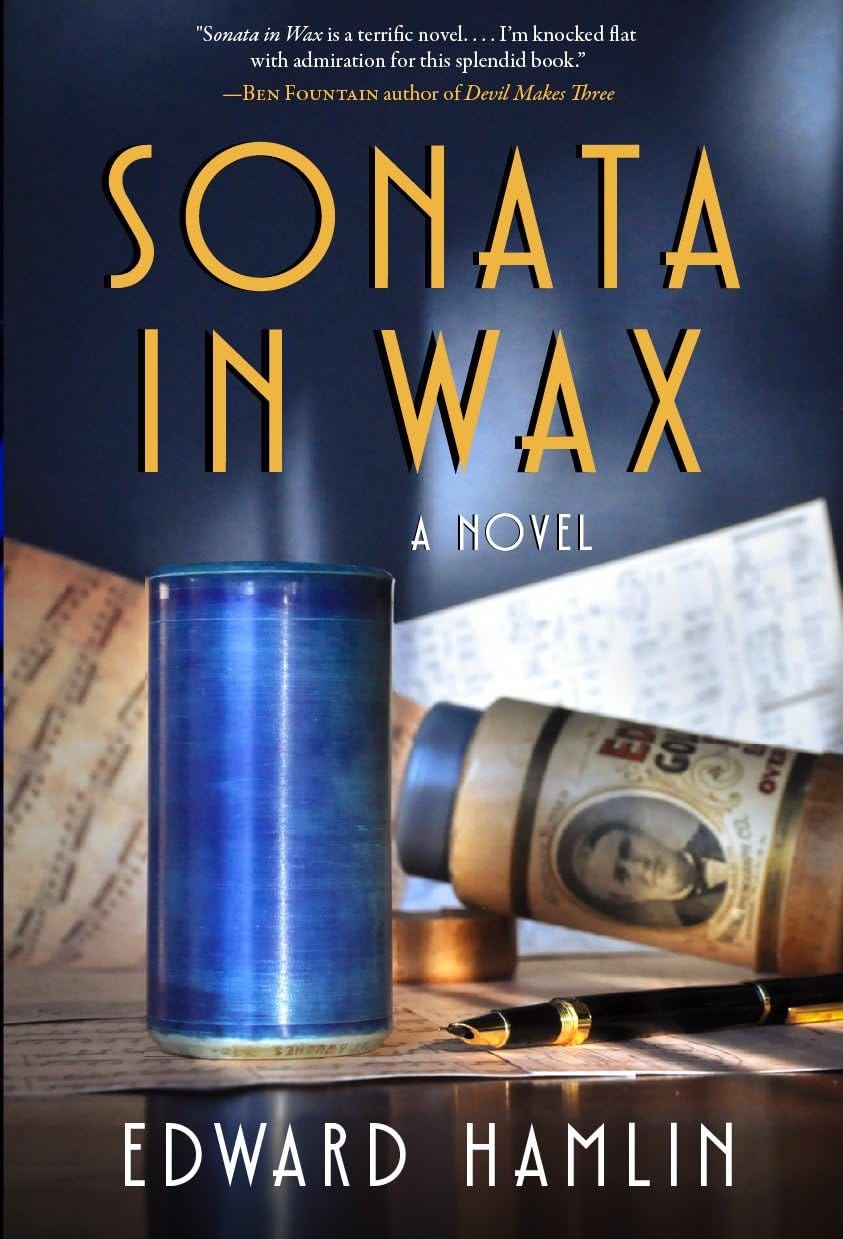

Read Edward’s short story collection, "Night in Erg Chebbi” or his novel:

Click the image to get your copy!

Q&A

Which philosophy or philosopher most aligns with your own beliefs?

As a younger man I devoured Merleau-Ponty, Husserl and Heidegger because that focus on direct lived experience, on understanding how the mind and body process the world, was something I needed at the time. In parallel I was going pretty deep into Buddhism, for somewhat the same reasons, and that’s where I ultimately found a philosophical home. It’s why I try to write embodied fiction, robust with all five senses and then some, and why I’m always a sucker for an author who can get me out of my head and back into the immediacy of the lived moment. It's something I aspire to do but often fail at.

Is there any standard publishing or writing advice that you disagree with? Or any standard advice that you feel is too often neglected?

Not to walk into a hail of bullets here, but I strongly disagree with the notion that you can’t write about people who aren’t of your own cohort, whether that’s in terms of race, ethnicity, sexual identity, profession or anything else. Because I believe that the core practice of fiction is radical empathy, I don’t think fiction is even possible without the freedom to write outside your own narrow little world. Writing about people who aren’t just like you isn’t cultural appropriation, if you do it with honor and respect; it’s communication and connection.

But only when done with integrity, of course. At root this is an ethical question, and a matter of first doing no harm. We all know the horror stories and they’re bad. The whole debate about appropriation didn’t come from nowhere; it’s a reaction to generations of authorial malpractice and straight white male cultural bias. I get that. What that says to me—as a straight white male—is that my solemn responsibility as an author is to get it right, to make it emotionally authentic and evenhanded and true.

That’s why I try to have my work vetted by people who are embedded in the context I’m writing about, if it doesn’t happen to be my own. The POV character in a story I published in Ploughshares (“Kaat”) was a Belgian lesbian, so I had a Belgian and a lesbian read it, though not a Belgian lesbian per se. When I wrote about a soldier and a military dog paralyzed by PTSD, I had the story vetted by an old friend who was a brigadier general with tours in both Iraq and Afghanistan; he in turn had it read by the officer who is in charge of the K-9 program for the entire Army. I haven’t been to war, but I’ve observed what war does to soldiers and I care about it deeply; by writing the story I do think I came to understand it a little bit better. But because it’s not my direct experience, I would never have dared send such a story out without proper due diligence and a solid reality check. I’m so glad I wrote it, and Colorado Review published it, because I’ve heard from multiple veterans who found it cathartic and moving, including my first readers in the Army.

So for me, the whole screaming match over who gets to write what can’t end soon enough. We all need to calm down and have a more constructive dialogue, which I do think is starting to happen. I don’t think anyone in the literary world wants to kill off the medium of fiction, which is such a powerful tool for mutual understanding. In the mean time I plan to keep doing what I do.

Is your process for writing philosophical fiction different from the way you approach other works?

Yes and no. I like to work in grey areas of all kinds, liminal areas, and often that leads me into some kind of moral or ethical ambiguity. To me that’s when a story really splits open and shows its guts—what it’s really about, regardless of what I thought it was about. There’s an edge there that I really like, because it almost always feels perplexing and productive and important.

It’s not exactly a method, but I do tend to throw down these challenges for myself and trust that my characters will help me work through them. My novel SONATA IN WAX is all about a lie and how the liar feels his way toward making it right; I didn’t know how he’d pull it off until he did, and a number of readers have reported the same experience. When those moments come while writing it feels like you’ve grabbed the bare end of a live wire. I love that.

Edward Hamlin is the winner of the Nelson Algren Award, the Iowa Short Fiction Award, the Nelligan Prize and the Colorado Book Award. Pulitzer Prize finalist Karen Russell called his prizewinning short story collection, NIGHT IN ERG CHEBBI AND OTHER STORIES, “sweeping and intimate and awesomely confident.” Publishers Weekly named NIGHT IN ERG CHEBBI a “memorable read from a writer with considerable talent.” About Hamlin’s debut novel, National Book Award finalist Ben Fountain said: “SONATA IN WAX is a terrific novel—immersive, compelling, smart, the story propelled by a cast of complex, full-bodied characters and the author's absolute mastery of the musical worlds he conjures…I'm knocked flat with admiration for this splendid novel.” Kirkus Reviews called it “a deeply realized tale of the power of music and the anonymity of history.”

Since 2012 Edward Hamlin has published more than twenty-five stories in Ploughshares, Missouri Review, Colorado Review, Bellevue Literary Review, Chariton, the Chicago Tribune and elsewhere, garnering three Pushcart Prize nominations along the way. His work has been shortlisted twice for the Bridport Prize (UK) and has been a finalist for the Flannery O’Connor Award, the Grace Paley Award, the Narrative Story Prize, the Raymond Carver Award and others. Stories of his have also been performed on stage and published by Audible.

A New York native and an accomplished composer, Edward Hamlin spent his formative years in Chicago and now lives in the Colorado foothills.

Hamlin is 100% correct. Cultural appropriation is a false and dangerous idea.