Educators, find out how to get a free copy of a themed edition.

If you enjoy these stories and want to support writers and what we do, you can always subscribe to our monthly magazine via our website (digital or print), or via substack.

Also check out our free partner ebook downloads.

Thanks for reading, sharing, and re-stacking this post!

Tina

Take the poll for this week’s story, “A Change of Verbs”:

(It’s completely anonymous…and fun!)

Last week’s poll results:

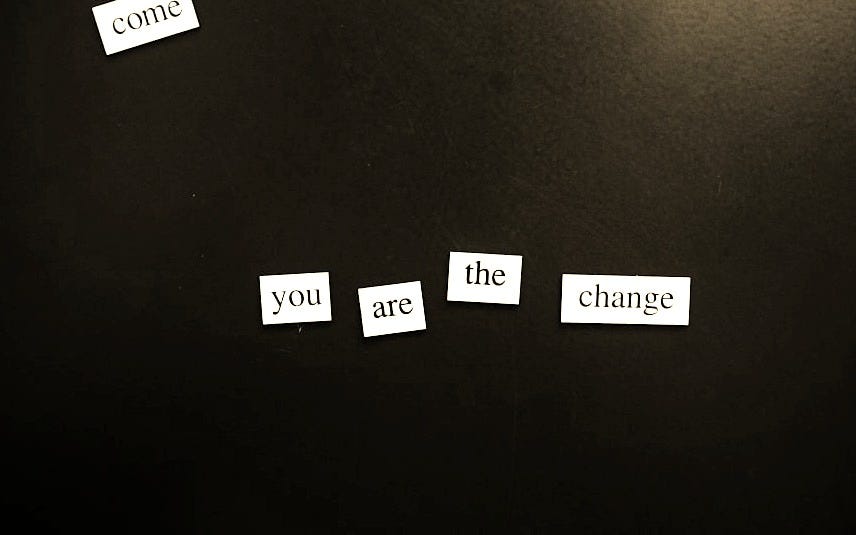

A Change of Verbs by Tom Teti

A change of verbs can be a boon to a man’s life. Such was the thought that seized Simon McCalla in mid-bite of his double-toasted English muffin. It was Friday, precisely 7:52 AM by the clock on the range.

“I said, what time is it?” yelled his wife from the closet. She rummaged for something.

“Are you there? What in creation are you doing?”

“Sorry,” he said. “Seven fifty-two, ah, three.”

“I can’t hear you.” Her bark was muffled by the winter coats. She appeared in the doorway to the kitchen, pulling up her pantyhose and pulling down a slip under her skirt. Her legs were still sturdy. “What good does it do me to ask the time if I have to come in here to hear you?”

“Uh, seven fifty-three, ah, four.”

“Yes, I see that, now. I have a meeting at the hospital with the Chief of Surgery. He’s an idiot but a punctual one.” She shook her head, inhaled through her nose and went back for a jacket. “What’s the temperature?”

Simon, back to his English muffin, twisted in his chewing to get a read on the thermometer mounted on the side of the shady window. “Sixty-two,” he replied, and added his traditional caveat, “but this thermometer is unreliable, it’s outside, you know, and in the shade.”

“Did you hear the weather?” his wife demanded to know from deep within the same rack of coats.

“Sorry.” He chewed. “Do you want the radio on? Carol?”

She muttered along in such a way that he could not quite be certain whether she had heard him or not. “I’m cold now, I just don’t know if it will stay that way... Oh, I’ll just wear this.” She emerged from the closet with a short, camel hair jacket. She bustled into the kitchen, dropped it onto the stool in front of which sat her rapidly chilling toaster waffles, and went to the powder room putting on dangling pearl earrings which he knew had been in her hand since she left the bedroom.

“Would it be too much to wait for me to eat one of these mornings?”

“You...” He paused. “I can never tell if you are actually wanting to eat or not,” he said, thinking of her ritual two bites at the counter, standing up, and tossing the rest of the cold waffle into the sink and down the disposal. Of course, she never heard anything he said unless he got up and went to the doorway, because the powder room light was connected to a very noisy exhaust fan. He stayed on his stool and finished his muffin. It was 7:58. At 7:59, exactly one minute before he had to leave the house, she would ask the daily question. Simon pondered his answer more intently than usual.

He watched the powder room. Carol’s shoulder and elbow could be seen, as well as her handsome, forty-something derriere in that straight black skirt, the backs of her ankles in grey tights, and the stacked heels of her shoes, but not her face. He gulped the rest of his coffee, the dispiriting decaf she insisted they switch to oh-so-many months ago, and rose to face his fate. On schedule, it came.

“What are your plans for today?”

Simon pushed his rimless glasses up onto his nose. He stalled for time.

“Well, I teach the seminar, this morning.”

“Yes?” she called.

“And I have a class at 1. And a meeting for the college newspaper at 2:30.”

“Darling, I know that you have a job, that’s not what I’m asking. We go through this every day.” They were his usual answers and she anticipated them; they could be heard without turning off the fan in the powder room. “I am asking what you are doing after that.” She prattled on about the dog and taking him round to have Dr. Berks look at his coat and confirm that the supplements he’d dispensed were working, as they seemed to be.

Simon gazed out the kitchen sliding doors at the dog, tethered to a come-a-long. He sat in a restless posture, panting with his tongue hanging out of his mouth, and looking into the kitchen as if he knew he was the subject of some eleventh-hour decision.

“Chiku must be evaluated before we continue with more vitamins,” Carol said. “You need to take him.”

It was not a drastic situation. It wasn’t even a problem situation. The dog was clearly fine. The challenge would then become, could he, Simon, finish his sentence before being sentenced himself?

The day ahead passed through his mind as he would like it to happen: a stimulating seminar with piquant seniors on the landscape of the body in 19th century literature (a cup of Sumatra off to the side); stilton and walnuts on spring mix at the Hound and Duck, while reading The Luck of Roaring Camp; class with hopeful juniors on America’s Solitary Western Voices; a meeting at the newspaper where he would deftly quell a movement on the part of some of the female writers to cease promoting sports; afternoon half-caf from Perfumes of Arabica; a sit on the slab bench under the tulip poplar at the pond, musing about the qualitative effect of one’s first sight of something beautiful; then, after scribbling the opening of a sonnet on the back of an envelope, he would go home, when the sun had a few minutes left, and he and Carol would walk the dog, prepare branzino with a butternut squash risotto, and open a bottle of Chardonnay, probably Australian, with fire in the fireplace and a movie, perhaps.

It was an old picture, meaning a picture of oldness, settled and two steps from a yawn, perhaps, but one that pleased him, made him feel warm, content, loving and loved. He wished for it, but pictured it as he feared it would unfold: seniors having Sumatra, decaf for him, and checking their cell phones to see how much longer until class was over; failing to say that he had other plans when one of the faculty asked him to have lunch and discuss curriculum; juniors cutting, because it was Friday and they could get drunk before dark; a bellicose argument between two sides of the newspaper staff and Simon hearing himself say that their concerns may be valid and should be addressed at student government; rushing home to take Chiku to the vet so the vet could say he looks great, then rushing back to prepare dinner, not the branzino because there wasn’t time, but defrosted shrimp from the freezer, sautéed as some kind of quasi-scampi over linguine; Carol calling to say she’d be late, then crashing in exhausted, full of questions and directives, telling him the fire’s too hot on a night like this and she doesn’t want any wine because she’s got a headache. Then, a movie, but she’d fall asleep at the thirty-one minute mark, her head crooked in the corner of the sofa, the dog asleep at her feet.

The moment had come. Simon took his tweedy jacket with the suede elbows from the hook by the back door, glanced toward the dog who was eyeing the door with a martial arts kind of calm, ready to break the spell at the drop of a leash, and marched to the powder room. As his wife returned her makeup to its pouch and turned off the light and fan, Simon heard himself say, in the deafening quiet, “I’m busy this afternoon. I’m going to walk by the pond and work on my sonnet.” He then gave her the expected peck on the cheek, turned and walked to the back door. His last vision of her was a modestly stunned gape as he pulled his cheek away from hers. Keeping his sensors alert for any protest on his exit, he tried as best he could to walk in a way he considered ‘normal’ and hoped it appeared the same to Carol, though, internally, he was like a geyser about to spray. With his hand on the knob, he heard her say, “What about dinner?”

“I’ll be back,” he said, perfectly in stride through the door, and shutting it behind him.

The air felt brisk and lively. The sun glinted off his glasses but today, it didn’t annoy him, he craved it. He slipped into his jacket and clipped down the flagstones to the brick-lined sidewalk on his way to the college. This was the way a professor was supposed to feel as he began his day: hale, hearty, of sinewy mind and assured affect, headed for a day of scholastics and the acrobatic engagement of ideas. He waved to a man across the street. “Hello!” he called. The man looked back curiously, held up a finger of acknowledgment and frowned. Simon smiled. “Surprised him,” he chuckled.

In ten minutes he was entering the old double window doors of Perfumes of Arabica. A very thin student, a girl with piercings in her eyelids and nose and dyed hair of an unnameable color, was scooping beans from a plastic-lined burlap bag that had Kenya stamped on it. She cheerily asked him if he wanted “a small decaf to go?”

Do not waver, do not deliberate, not today, thought Simon, as he imagined himself saying what he usually said: “That Sumatra smells good, but I suppose I shouldn’t, I guess I’ll have the decaf.” Instead, he told her: “I want Sumatra, today.”

Her eyebrows went up, rings and all. “Woo, Friday, the good stuff, huh?”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to After Dinner Conversation - Philosophy | Ethics Short Story to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.